COMS 4995 Advanced Systems Programming

Interprocess communication in UNIX

Pipes

Unnamed Pipe

#include <unistd.h>

int pipe(int fd[2]);

// Returns: 0 if OK, –1 on error

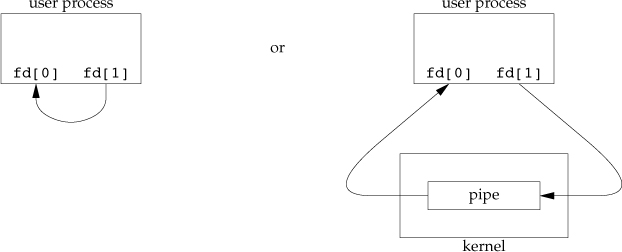

After calling pipe():

fd[0] is opened for reading, fd[1] is opening for writing

- OS kernel maintains a fixed-size buffer for the pipe

- Reader blocks if pipe is empty

- Writer blocks if pipe is full

- See

man 7 pipefor more details

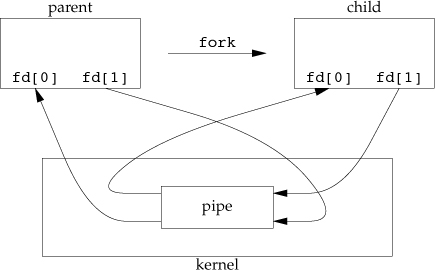

Recall that all open file descriptors get duplicated to the child process when a process forks. When a process with an open pipe forks, the child process inherits both the read and write ends of the pipe, as shown below.

Note that pipes are half-duplex, which provides one-way communication only.

fd[0] is for reading only and fd[1] is for writing only. A program can

choose one of the following semantics:

- Parent writes to

fd[1], child reads fromfd[0] - Child writes to

fd[1], parent reads fromfd[0]

If parent writes to fd[1], and then reads from fd[0] expecting to block

until child writes something, it actually ends up just reading back what it just

wrote. A full-duplex file descriptor, such as a socket descriptor, would

allow reading and writing on the same descriptor.

A program will typically close() unused ends of pipe after forking depending

on which process will read/write. For example, the code below has the child

process read from the pipe and the parent write to the pipe:

int fd[2];

pipe(fd);

if (fork() == 0) {

close(fd[1]); // close unused write end

// ...

read(fd[0], ...);

} else {

close(fd[0]); // close unused read end

// ...

write(fd[1], ...)

}

Note the dependence on fork() for sharing the pipe via duplicated file

descriptors. Two processes can communicate through an unnamed pipe only if they

are related processes (i.e., parent and child).

connect2 demo

The following program demonstrates how a shell would stitch together two

processes to form a pipeline (e.g. when a user runs p1 | p2 on the command

line).

Note the usage of dup2(), which allows you to target a specific newfd to

copy oldfd into. If newfd is already taken, dup2() atomically closes

newfd before copying oldfd into it.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

int fd[2];

pid_t pid1, pid2;

// Split arguments ["cmd1", ..., "--", "cmd2", ...] into

// ["cmd1", ...] and ["cmd2", ...]

char **argv1 = argv + 1; // argv for the first command

char **argv2; // argv for the second command

for (argv2 = argv1; *argv2; argv2++) {

if (strcmp(*argv2, "--") == 0) {

*argv2++ = NULL;

break;

}

}

if (*argv1 == NULL || *argv2 == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "%s\n", "separate two commands with --");

exit(1);

}

pipe(fd);

if ((pid1 = fork()) == 0) {

close(fd[0]); // Close read end of pipe

dup2(fd[1], 1); // Redirect stdout to write end of pipe

close(fd[1]); // stdout already writes to pipe, close spare fd

execvp(*argv1, argv1);

// Unreachable

}

if ((pid2 = fork()) == 0) {

close(fd[1]); // Close write end of pipe

dup2(fd[0], 0); // Redirect stdin from read end of pipe

close(fd[0]); // stdin already reads from pipe, close spare fd

execvp(*argv2, argv2);

// Unreachable

}

// Parent does not need either end of the pipe

close(fd[0]);

close(fd[1]);

waitpid(pid1, NULL, 0);

waitpid(pid2, NULL, 0);

return 0;

}

Named pipe (FIFO)

#include <sys/stat.h>

int mkfifo(const char *path, mode_t mode);

// Returns: 0 if OK, –1 on error

mkfifo() creates a new named pipe on the filesystem. A program can open() a

named pipe for reading or writing as if it were a regular file, but the call

blocks until another process opens the other end of the pipe.

I/O on a named pipe will behave just like I/O on an unnamed pipe, as described

above. That is, read() will block if the pipe is empty and write() will

block if the pipe is full.

Unlike unnamed pipes, however, named pipes can be used for IPC between unrelated processes because two unrelated processes can simply open the same named pipe on the filesystem. Thus, the named pipe serves as a rendezvous point for the two unrelated processes.

Memory-mapped I/O

Recall that the mmap() system call allows you to create memory mappings. We

covered the semantics of mmap() (here).

With MAP_PRIVATE specified, the mmap() system call creates a memory mapping

for the calling process only. A private file-backed mappings gives the process a

private copy of the file in memory and modifications to it are not written back

to disk. A private anonymous mapping has the effect of simply allocating memory

for the process.

With MAP_SHARED specified, the mmap() system call creates a memory mapping

with the intention of it being shared with other processes.

- A shared file-backed mapping allows two processes to map the same region of a file on disk into their address spaces, and modifications to mapped memory in one process will be reflected in the other process and also eventually on disk. Therefore, a shared file-backed mapping can be used by two unrelated processes for IPC since they use the file on disk as a rendezvous point.

- A shared anonymous mapping removes the file on disk from the equation, so it can’t be shared between unrelated processes as there is no rendezvous point. Instead, shared anoymous memory mappings can be used for IPC between two related processes. The parent process can create a shared anonymous memory mapping and the child process will inherit it when the parent forks.

POSIX Semaphores

Recall that POSIX semaphores are also available in both unnamed and named flavors. We covered the semantics of POSIX semaphores here.

Named semaphores can be used to synchronize multiple unrelated processes because the semaphore file on disk serves as a rendezvous point.

Unnamed semaphores can be used to synchronize multiple threads or related processes. For the latter, you must ensure that the semaphore is placed in a shared memory region accessible by all the processes.

The following example program demonstrates a parent and child process incrementing a counter variable in parallel. An unnamed semaphore is used to synchronize access to the counter. The counter and the semaphore are placed in shared anonymous memory.

#define LOOPS 1000

struct counter {

sem_t sem;

int cnt;

};

static struct counter *counter = NULL;

static void inc_loop() {

for (int i = 0; i < LOOPS; i++) {

sem_wait(&counter->sem);

// Not an atomic operation, needs lock!

// 1) Load counter->cnt into tmp

// 2) Increment tmp

// 3) Store tmp into counter->cnt

counter->cnt++;

sem_post(&counter->sem);

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

// Create a shared anonymous memory mapping, set global pointer to it

counter = mmap(/*addr=*/NULL, sizeof(struct counter),

// Region is readable and writable

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

// Want to share anonymous mapping with forked child

MAP_SHARED | MAP_ANONYMOUS,

/*fd=*/-1, // No associated file

/*offset=*/0);

assert(counter != MAP_FAILED);

// Mapping is already zero-initialized.

assert(counter->cnt == 0);

sem_init(&counter->sem, /*pshared=*/1, /*value=*/1);

pid_t pid;

if ((pid = fork()) == 0) {

inc_loop();

return 0;

}

inc_loop();

waitpid(pid, NULL, 0);

printf("Total count: %d, Expected: %d\n", counter->cnt, LOOPS * 2);

sem_destroy(&counter->sem);

munmap(counter, sizeof(struct counter));

}

Caveat on portability: macOS does not support unnamed semaphores!

Last updated: 2024-10-09